A dying art at Warrock

Art takes a never-ending variety of guises. Given the number of artists extolled for their drafting skills, it seems only reasonable that good drafting might itself be considered a legitimate art form.

This is especially so when, as in so many artistic representations, a tale of some note accompanies the work. It is even more important given that it is a dying skill, one that has been slowly but surely replaced by the cyber skills of computer assisted drafting.

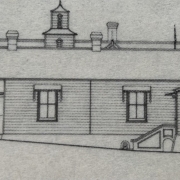

Take the measured drawings of the Warrock farming station north of Casterton overseen by Geelong architect and former Deakin University lecturer Lorraine Huddle.

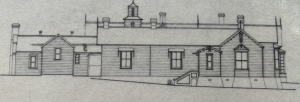

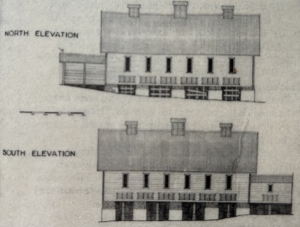

The striking plans, elevations and sections prepared by 100 Deakin fourth-year architecture students for this project, undertaken in the early 1990s, presently live within the Special Collection of the Deakin woolstores campus library.

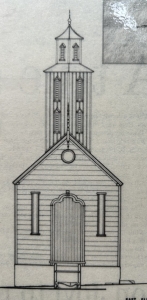

All up, there are some 230 drawings of the past settlement’s belfry, bull shed, homestead, shearing shed, shearers quarters, lavatories and much more. The drawings were worth an estimated $300,000 some 20 years ago, and were used by Heritage Victoria to assist in the station’s restoration.

The wider Warrock collection at Deakin includes monographs, maps, music, ephemera and pamphlets. However, it is the drawings that really strike the observer. Most are rendered in ink, some in pencil, and display inordinate details which at times extend as far as nail holes in timber weatherboards and often individual bricks.

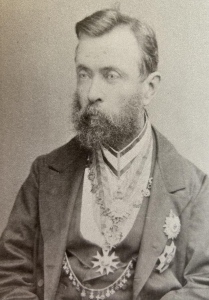

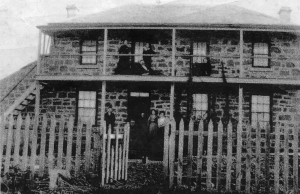

The measured drawings were used for the restoration of dozens of buildings on the property, a Western District pastoral station about 30 km north of Casterton built by Scottish cabinet-maker George Robertson from the 1840s onwards.

It is considered Victoria’s, perhaps Australia’s, most important collection of farm buildings and includes 57 structures mostly built of sawn timber.

The complex sprawls across a gently rolling parkland of ancient river redgums with its grainstore, dairy, bacon house, blacksmith shop, bullock byre, branding shed and numerous other buildings reflecting the life of an isolated sheep station where all the necessary essential to life and such circumstances had to be grown or stored for long periods.

Other buildings in the complex include a pigsty, privies, stable, kennel, hayshed and hay barn, branding shed, foot dip, slaughterhouse, skin shed, cow bail, duck run, coach house and a cottage.

“Some of the buildings are just marvellous, they’re gorgeous,” said Huddle. “Also, it’s a dying art. All the Warrock drawings were done by hand. The students were very, very keen. The place got them in. There was no electricity there, only in the main house and a little cottage.

“One night I went walking about 10.30 and saw some lights in the conservatory. Students had placed candles in the dirt of a garden bed and were working on the drawings. That’s how keen they were.”

Huddle says George Robertson’s cabinet-making skills were reflected in the detail of numerous buildings at the station.

“You can also see his strong Protestant work ethic expressed in these buildings,” she says. “The bell tower, for instance, looks like a little chapel but it’s just a bell to call people to work.

“Time management was a pretty important part of that work ethic and while Robertson worked hard all the time, he treated his workers very well. He gave them good accommodation and looked after them a lot – but he expected them to work hard too.”

The original version of this article was published in the Geelong Advertiser 18 March 2001.

.

.