Australia hosts an inordinate number of ghost towns peppered over its plains, through its mountain ranges and across its desiccated deserts. Thousands of them.

Bustling social communities full of families, workers, business, schools, sport and more have vanished to the inexorable march of progress, to market changes, technology and dwindling resources. What were once thriving places of enterprise, built on industries of farming, mining or in many cases gold, have quietly disappeared beneath the waters of history.

Little or nothing remains of most. Yet others, such as Werribee’s State Research Farm, in the southern Australia state of Victoria, have left an enduring and extraordinary legacy.

Some of the Farm’s original buildings remain, although in poor condition. But its core township of 30-odd houses that grew around an agricultural research facility has vanished. Likewise, the people, the families that lived, worked, played and grew up there have vanished into the ether.

Even the State Research Farm name has gone.

The Victorian Government set up the Farm for agricultural research and experimentation as the Central Research Farm in 1912 on 1167 acres. It was to respond to ongoing social problems from the earlier 1890s economic depression and be an institution for scientific advancement rather than a commercial enterprise. It changed its name in 1915 to the State Research Farm.

Plant breeders were the first scientists recruited because of a desperate need to breed better wheat and barley varieties to replace those bred in England. After World War One, the Farm trained veterans in the newest agricultural techniques. It delivered lectures and field demonstrations to convey the most contemporary farming practices. By the 1930s, the Farm’s scientists were regularly taking their findings to farmers around the State in various ways.

These included a show-stopper Better Farming Train, with experts and numerous carriages loaded with samples, examples, images and more. The train was a major event everywhere, with farmers and townsfolk descending on it like a major country fair. It influenced many farmers at hundreds of towns. At one stage, nearly every grain of wheat, barley and linseed coming out of Victoria had ancestors at the Farm.

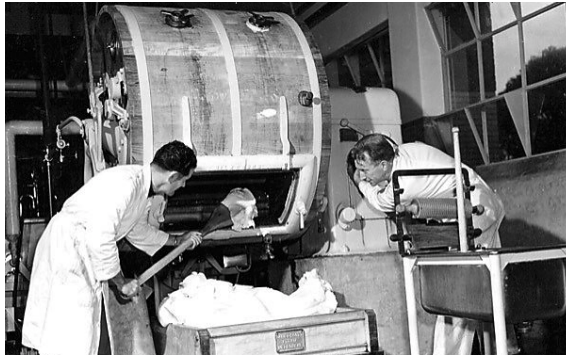

The Farm’s Dairy Institute opened in 1939 as a national dairying research centre and over the years, taught cheese-makers all over the world. It eventually grew to become Australia’s research institute for food overall.

In World War Two, the Farm produced vegetable seeds for local and international needs, and ergotine for shell shock and opium poppies to overcome a morphine shortage at the time. Women from the Australian Women’s Land Army were trained in farming practices.

University of Melbourne agriculture students lived on the experimental station for a year, where trained staff investigated agriculture and livestock husbandry problems thorough testing of experimental results under practical farming conditions.

The Farm quickly earned an enduring reputation for excellence. Its experiments to improve farming practices across a raft of areas delivered ongoing breakthroughs over many years in wheat, cereals, grasses, soil, crops, irrigation, fertilising, plant nutrition and natural pastures.

Its researchers helped improve livestock, dairy technology and milk yield, poultry, pigs, stud breeding, weather observations, tractor performance and farm infrastructure. Farm breakthroughs included IVF practices via artificial insemination, heart medical science via pig research, and dairy technology such as spreadable butter, flavoured yoghurts, milks and ice creams.

The Farm’s legacy continues in new and varied research pursuits in the much-altered Farm precinct today. It lives on in numerous agricultural practices and commercial products that emanated from a century of the Farm’s remarkable and far-reaching efforts. Not sure this paragraph should sit here?

The Farm is listed on Victoria’s Heritage Register because it illustrates a change in agriculture from European practices to practices specific to Australia’s climate and conditions. It contains fine examples of public architecture appropriate to the purpose and scale of its research and experimentation, including the Farm’s first buildings laid out in an H-configuration, first laboratory, fodder building, silos, dairy, stables, carpenters and painter workshops, an office, bagged grain store, grain storage tanks, shearing shed and former Melbourne Showgrounds pavilion. The listing gives the buildings the highest level of protection in Victoria.

The Farm is of scientific significance for its role in agricultural practices implemented and adapted around Victoria, Australia and internationally. It is significant for its association with leading scientists such as its founder Dr Samuel Cameron, Victorian Director of Agriculture, Emeritus Professor Alan Trounson AO, renowned internationally for his work in IVF, and Professor Jock Findlay AO’s research in sheep reproductive.

Scientists like Hugh Gordon, Alan Raw, Gwen Hotton, Leo Bartels and others bred plants and released them to great benefit to farmers. Agronomists Gwen Hotton and Leo Bartels made pasture breeding their life work and with Barry Dimelow, sought pasture varieties that responded to the autumn rains and grew well. This was on the back of Senior Geneticist Alan Raw with years of experience in wheat breeding and a gift in picking the right plant where he selected and bred more than 90% of the wheat grown in Victoria.

And now, thanks to a powerful community effort, the Farm’s history of intellectual rigour and ground-breaking research and application is being saved for posterity. Celebrated in fact.

Over the past two years, a vibrant catalogue of the State Research Farm’s scientific achievements, its characters, their day-to-day lives, social ties and activities has been amassed by a dedicated group of chiefly volunteers. The research team established State Research Farm Community Facebook and Instagram social media pages to activate the lost community of past Farm residents and workers and their families, and rebirth it through oral history interviews, images, collection of memoirs and film, Out on the Farm.

This catalogue, this collection of spoken and written stories and images, is a personal voyage into the homes and haystacks, workshops and woodheaps, the laboratories and lifestyles, by the people who made up the Farm. It is a quintessentially Australian story about a ghost town that had a softly spoken but powerful impact across agriculture, industry and commerce.

The recollections, videos, photos, clippings and memorabilia are a treasure trove of Australiana. Kids climbing trees, falling out of trees, hunting snakes and tadpoles, building cubby huts and all but running wild. Parents and children alike chopping wood, collecting milk and bread deliveries, watching animal births over the back fence.

Scientists, all the while, were developing new practices and technologies that would transform farming and agricultural-related products. At the same time, laboratory staff, field workers, tradespeople beavered away in all manner of industry.

The investigation not only preserves and celebrates the achievements of the Farm but, importantly, the strong community behind those achievements. It assists in the conservation of the Farm’s heritage and provides a legacy of learnings into the belonging and social cohesion that exists within such communities, learnings vital for future sustainable urban development.

The study provides immeasurable insight into how such communities thrive alongside industries they served. It can teach us of social and economic development in the past, and the challenges and evolution these communities faced.

We now have a repository of resources of the Farm for research, education and other uses. The Farm’s profile and its hub of heritage listed “H” buildings have been elevated in the public arena. Enormous potential exists for the preservation and development of this central site as a creative, community, historical and tourism space.

What we have is one of the great unsung stories of a remarkable but modest Australian community that really changed the world. Our hope is as Dr Graeme Mein says in the film, Out on the Farm, that this historic site becomes a vibrant centre for science, education and community once more – a fitting way to celebrate the Farm’s living heritage.

This article, co-authored with Dr Monika Schott, appeared in The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage Bulletin Number 101, 2023.