Bit strange, at times, trying to reconcile the many images of very old Lorne buildings with the ultra-contemporary designs of today.

Black and white, broody and artistic as it might be, doesn’t fully convey the reality of the 19th century ocean-bush collision.

And new buildings referencing the architecture of the past in voguish designs, well meaning as they might be, don’t really hold up, let alone replicate the privations of life 150 years past.

Romanticism about the past is very much that, romantic, people forget the smells. All of which is fine but it’s refreshing to find a half-way point where that sense of yore connects kind of softly with the present.

Somewhere between the leviathan horse-drawn coaches of the past fording a stony Erskine and the latter-day drone videos buzzing the Otways’ saddles and swales, and rugged coastal beaches and defiles. Between the antediluvian jalopies negotiating the Great Ocean Road’s initial goat-track incarnation and today’s swank Euro sedans and SUVs gliding along its gentle cambers.

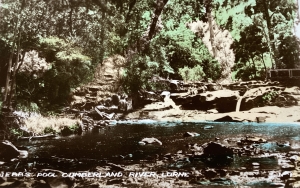

Several old photos dropped anonymously on my desk do pretty much that.

They’re from somewhere between the wars I suspect, late thirties, maybe into the forties. Coloured pics, tinted with fairly primitive looking tones – not so different, perhaps, to more recent apps used to ambitiously colour old monochromes – but relatively believable for the main part.

What they do provide, however, is a living-memory connection between the seriously heavily forested faraway getaway of the 1800s, still occasionally found in old framed pics on Lorne store walls, and the present day.

The tiny town, peeking out from the bush to the ocean, hosts cars with Chicago-style running boards and arched wheel-guards which sit neatly alongside old timber verandas and balconies and corrugated iron roofs.

Overly green spaces along the foreshore attest to a fanciful level of civic irrigation. Similarly, gravel roads oddly match the colour of the beach sand and bathing boxes. The seawater’s turquoise tones are overdone, too.

Waterfalls, waterways, bridges, birds-eye clifftop views, bush pools and beachfront scenes all appear quite dated but it doesn’t matter. What the images show is a recognisable version of the town in its fledgling form. Something within reach of both Lorne’s beginnings and its present.

The images are curious, quaint, real. The bare patches between houses, the scarcity of houses, the few streets, the closeness and density of the encroaching bush – and the ever-attendant fire menace it presents.

Rudyard Kipling gushed about Cora Lynn and the Erskine – ‘Take the flower and turn the hour, and kiss your love again! – breathing down his neck in the tiny Lorne of the 1890s. These images convey a similarly intimate co-existence in a fashion more familiar to 21st century travellers.

It’s not so hard to relate to the quicksand deaths of the young Lindsay brothers in 1850 near the present-day suspension bridge over the Erskine’s debouchment and the shock they would have caused in the tiny hamlet.

It’s also a little easier to also suspect Lorne’s early isolation as an incubator for folklore and other curiosities attached to the region – the Otways black panther, carnivorous snails and spotted quolls, surfers’ Big Kahuna wave-maker, bunyips, the odyssey octopus beneath the pier and the Louttit Bay seadragon.

They were a superstitious lot back in the day, after all.

This article appeared in the Geelong Advertiser 27 January 2025