Bit sad how poor Meritamun’s lot have been demonised and stereotyped by Hollywood over the years.

If you took the Boris Karloff version as writ, you’d think she’s a ghoulish monster from beyond the grave. If you took on board the Lon Chaney version, even her delicate hand would be a devilish murderous aberration.

Fact is she’s more like the riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma that Churchill once suggested of Russia, and which cartoonists portrayed with him eyeballing a map of Russia with The Sphinx superimposed on top.

Meritamun is 2000 years old, give a take a century or two. She first came to light at the Geelong Free Library and Museum, donated by one Mr E.J. Haynes in 1937.

As a head. A shrouded head.

She arrived with a separate shrouded hand. Both reportedly removed from the Valley of the Kings near Luxor, ancient Thebes, south of Cairo. Quite the prize exhibit, too, even rating a mention in despatches in Melbourne’s The Argus.

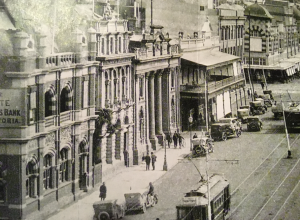

But within just two decades, she disappeared. The metacarpals, too. Not that anyone at the time knew she was a female. The beautifully colonnaded museum, on Moorabool Street, was torn down and its contents distributed lord knows where.

Geelong Free Library and Museum

Swags of stuff went sideways. Lots to the tip, other stuff to the Lunan House Teachers’ College in Drumcondra, the rest of it to parts unknown. The late Peter Alsop, former president of the Geelong Historical Society, suggested some artefacts perhaps made their way into private collections.

Whoever had the mummy, however, was keeping mum. I only tripped to it with a fanciful story hunt on Google for anything resembling Geelong and Egypt 1937. Wanted an Indiana Jones connection.

Nearly fell over when it threw up a Trove link to The Argus reference.

It set me on a lengthy hunt for anything on Haynes, the old museum, Egyptologists of the era, anything that might offer a clue to the mysterious mummy. Scribbled a few missives here and there but found nothing until, about 10 years later, Geelong doctor/archaeologist Peter Mayall, tracked me down.

He’d been studying with the University of Melbourne and sent a message: “You’ve got a mummy’s head and hand, and you don’t where they went. We’ve got a mummy’s head and hand, and we don’t know where they came from.”

Almost felt like a Howard Carter moment, resolving the puzzle, although its provenance wasn’t fully resolved. The uni thought the mummy’s head and hand were part of a collection owned by a Professor Frederic Wood Jones, who undertook archaeological work in Egypt before he became head of anatomy at MU in 1930.

But all his stuff was from Aswan, a couple of hundred kilometres from the Valley of the Kings where the mummy purportedly originated.

Fascinating place, by the way, the Valley of the Kings. Home of Tutankhamun’s tomb with rampant baboons gracing its walls and advertising his fertility.

Check out the subterranean wonderlands of various Rameses if you’re ever in the vicinity. Likewise, the temple of Hatshepsut and the Colossi of Memnon. A word of caution, they might just do your head in a little.

Discovering Melbourne Uni had the mummy wasn’t the half of it, though. Not by a country mile. They’d been busy with, among other things, a multi-discipline crew running CT scans on the skull and hand.

The jaw’s size and shape, the narrow roof of the mouth and rounded eye sockets were give-aways to the mummy’s gender. They discovered the mummy was female; a young woman somewhere between 18 and 25 and afflicted by bad teeth, abscesses, missing teeth

Her skull’s bone structure suggested anaemia. The arm was similarly determined as female, and both head and limb were carbon-dated to the Ptolemaic period between 226 and 159BC. It was a time when Greek influence, and more sugared food, was strong. Nothing new, it seems, about junk food.

The linen bandages were identified as Egyptian by electron microscope and micro-nanometer radiation. Next, they 3D-printed a replica skull of what lay beneath the mysterious brown bandages.

A forensic sculptor then came on board to rebuild what this girl, separated in eternity from her body, may have looked like in life. The facial reconstruction resurrected a stunning young woman with features oddly familiar and surprisingly modern.

And they gave her a name: Meritamun, or beloved of the god Amun.

The scientists have been at it since with endoscopic surgery to extract DNA, carbon and nitrogen isotopes, pathogen analysis and the likes that might unearth more details about Meritamun.

The one mystery of the mummy’s head they haven’t been able to figure out; just exactly how she wound up with them.

This article appeared in Geelong + Surf Coast living magazine Spring 2024