Model farms, experimental farms and research stations have played a curious role in Australia’s agriculture.

Most are now in the great beyond, their impact largely forgotten, their physical heritage reduced to dust or ruin. Yet their legacies live on in new technology and commercial enterprises their early work helped drive.

Marshall’s Sparrovale Farm, in its day, was considered of huge benefit to Victoria’s farming communities. It provided a solid example of providing a pure milk supply profitably while showing that agricultural science could successfully exploit what was deemed near-barren land.

Not bad going for an old flood-prone racetrack but Sparrovale’s 1907-1933 life as a Geelong Harbour Trust model dairy farm was short-lived. It was rarely out of the news, constantly under attack or ridicule and, even within its own operations, subject to acrimonious differences.

Today, the site’s still proving contentious as owners and the city council square off over a compulsory acquisition price-tag for what is now the Sparrovale-Nubitj yoorree wetlands. The herons, terns, sharp-tailed sandpipers, ducks, stilts and brolga inhabiting the area these days are a far cry from the horseflesh back in the 1840s and the 200-odd cows of a century ago.

The farm came about when the harbour trust, created in 1905, was granted the old racecourse by the State government. Sniffing a quid, the trust drained the flats and within two years had a full-blooded dairy farm up and running.

Ostensibly, the 1100-acre Sparrovale Farm was going to be a State dairy college, one of several model farms the Department of Agriculture kicked off at Werribee, Rutherglen, Wyuna, Ballarat and Bamawm, as well as a school of horticulture at Burnley in Melbourne.

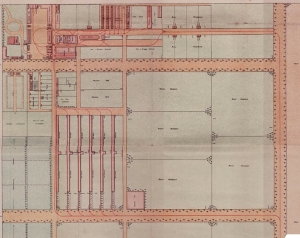

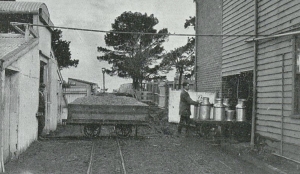

In fact, it was rather broader in scope and admirably equipped with all manner of ag-infrastructure and gear: milking shed, creamery, cool store, boiler house, student quarters, pigsties, stables, stallion yards, engine shed, garage machine shed and shop, seeding shed, pens, feed and coal sheds, manager’s house, a tramway between buildings, engine shed, silos by John Monash.

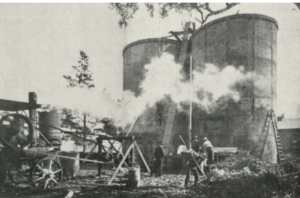

The latter, the silos, were a bone of contention between Monash and the farm’s engineer overseer, A.C. MacKenzie of the harbour trust. The cement content of the mix, the silos’ external finish, liquid and ensilage gas leaks, sweating …

Despite this, they managed to hold some 800 tonnes of maize ensilage between them, enabling non-stop year-round milking, a rarity in the day. Today, there are some footing ruins and, like the rest of the farm, little else. The short-lived glory days, if that’s what they really were, are long gone.

The harbor trust’s investment in a non-harbour enterprise didn’t sit well with Geelong’s burghers and, ultimately, it failed to prove itself a profitable concern. A withering 1933 auditor-general report led to a harbour trust restructure and the sale of Sparrovale to private interests a couple of years later.

The 500-hectare wetlands, together with Lake Connewarre and Hospital Swamp, are part of the largest area of native vegetation in Geelong, boasting numerous types of plants, including salt marsh, sub-saline marsh, lignum swamp, and freshwater wetlands. The wetlands are also an integral part of the Armstrong Creek growth corridor’s stormwater management.

Unlike other government farms, Sparrovale was not so much geared for research or teaching, as much as showing how a farm of its kind could run.

A bit of gamble, it seems, and a little ironic too, given the farm was named for Edward Rogers Sparrow, one-time secretary of the racing club.

Never really can trust those horses. As Sherlock Holmes avers: “Dangerous on both ends and crafty in the middle.” You can bet the farm on that.

This article appeared in the Geelong Advertiser 9 September 2024