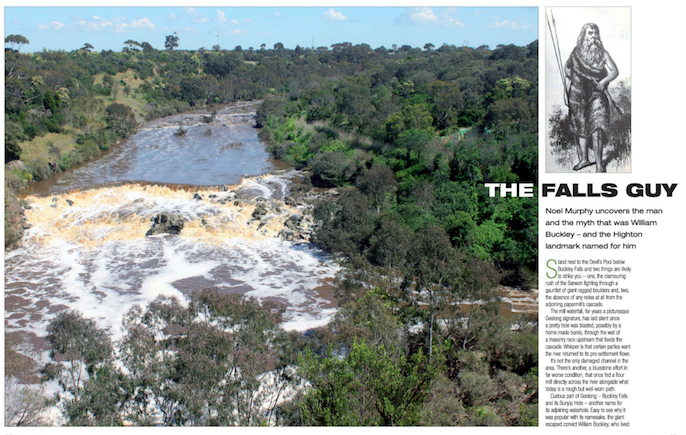

Stand next to the Devil’s Pool below Buckley Falls and two things are likely to strike you – one, the clamouring rush of the Barwon fighting through a gauntlet of giant ragged boulders and, two, the absence of any noise at all from the adjoining papermill’s cascade.

The mill waterfall, for years a picturesque Geelong signature, has laid silent since a pretty hole was blasted, possibly by a home-made bomb, through the wall of a masonry race upstream that feeds the cascade. Whisper is that certain parties want the river returned to its pre-settlement flows.

It’s not the only damaged channel in the area. There’s another, a bluestone effort in far worse condition, that once fed a flour mill directly across the river alongside what today is a rough but well-worn path.

Curious part of Geelong, Buckley Falls and its Bunyip Hole, another name for its adjoining waterhole. Easy to see why it was popular with its namesake, the giant escaped convict William Buckley, who lived among the local First Nation folk for more than 30 years.

The deep basalt gorge is a near-kaleidoscopic palette of geology, hydrography, nature, history, industry and culture – everything from drop-tail lizards, tiger snakes, legendary river monsters to a hill of buttons, artists and artisans, musicians and eateries.

Buckley, one of the most extraordinary figures in Australian history, should be myth or legend. His story sprawls across England, Napoleonic warfare in Holland, an appalling convict sea journey to the Antipodes, escape and near starvation 12,000 miles from anywhere familiar, before his resurrection as the revered Ghost Bloke Murrungurk among the region’s Wadawurrung people.

He roamed across the district for 32 years, marrying a local girl, protecting orphans and by his own account confronting terrifying violence and murder, even cannibalism. His favourite camping ground was reportedly the Barwon falls site now named for him. Little would he have realised a paper mill would be built there in the not-too-distant future.

Buckley was both feared and revered by his indigenous community, according to the first whites to encounter him. That encounter was historic – with Melbourne’s bounty-hunter founder John Batman’s expedition at Indented Head in 1835. The red-bearded six-foot-six wildman emerged from the bush to caution the party about the locals. He could barely remember how to speak English.

Buckley went on to become an interpreter and negotiator between the whites and blacks, but it was a brief tenure and he was unable to operate comfortably in either culture. He moved to Tasmania in 1837, marrying and working there until 1850 when he died after being thrown from his gig.

Right now, home-made IEDs notwithstanding, the Buckley Falls/papermill precinct is enjoying a vibrant resurrection from decades of neglect that saw its heritage buildings run down, even razed by fire, and serious riverside degradation.

People such as the friends of Buckley Falls have been weeding and revegetating the banks forever. Meantime, a small collective of business operators has slowly developed a village-like collective of art, lifestyle and cultural pursuits in the old mill buildings. Highton Rotarians are arranging walking tours through the area.

The mill is a mix of bluestone, red brick, corrugated iron, masonry and timber in numerous nooks and crannies across an undulating green landscape of gums, she-oaks, cypresses and giant figs. In its early incarnation, it was an austere-looking structure on a stark and uninviting rocky redoubt.

Today, it’s more a wonderland of industrial heritage, culture and heavily-greened nature. Even local witches turn out occasionally to celebrate the equinoxes and suchlike.

The paper mill’s back-story dates to 1878 when it first fired up. It employed up to 200 people, made 40 different types of paper for writing, printing, wrapping, blotting, from rags, sacking, used paper, rope ends and other refuse – as well as wood pulp. Buttons removed from clothing were dumped beside the mill and with time, dust, dirt and grass created what is known as Button Hill.

Ghosts are said to inhabit the precinct today, including a woman who lost a hand in an accident. Smaller orbs, tiny transparent balls of light supposedly connected to spirits, also reportedly show up in videos and photos taken around the mill. Shiver your timbers.

The Barwon Paper Mill cost Robert Miller somewhere between 40,000 and 50,000 pounds to set up. It’s had various owners; in 1888 it changed hands with the Victorian Paper Manufacturing Company, in 1890 it moved to H.L. Littlewood & Co.

It closed in 1923 and lay unoccupied for six years until the Hydro Manufacturing Company started up an iceworks and cool storage plant. In the war years, it was used to assemble sea mines manufactured at Ford and load them with explosive. Workers wore wooden-soled shoes to guard against sparks blowing the place to kingdom come. Decades since saw the mill’s buildings utilised for a variety of trade pursuits before its latest renaissance.

The mill’s silent rocky waterfall cascade was long the overflow of a kilometre-long water race to a Belfast-manufactured turbine that generated 300 horsepower of cheap electricity. It was built by 30 men blasting their way through solid rock.

An earlier back-story again shows the Buckley Falls riverbend on a rather intriguing map penned in 1861 by surveyor Richard Daintree of Far North Queensland fame. This shows Baum’s Weir and the long-gone flour mill upstream, Fyansford’s Swan Inn, which was badly burned in 2016, and the former Fairview Hotel atop Hyland Street. It also shows sandstone, basalt and quartz gravel quarries close to the Barwon and various gold shafts sunk around neighbouring Newtown.

Right now, the papermill water race is becoming a choked, overgrown channel in need of some serious TLC. I’m told the additional flow into the Barwon from the vandalism is disturbing the Bunyip Pool’s platypus inhabitants and driving several bird species, egrets and herons, from the vicinity.

But if they really are taking off, perhaps there’s something else at play. The name Bunyip Pool, Devil’s Pool, acknowledges the Wadawurrung’s traditional belief in a fierce creature inhabiting the Barwon, one Buckley himself said he saw several times.

Early white settlers were similarly spooked by bunyip accounts. In 1845, a wholesale scare ripped through Geelong striking fear into the fledgling Geelong settlement after a giant petrified bone was identified by local Aborigines as belonging to a bunyip.

The hysteria wasn’t helped by reports of savage attacks on animals around the district including a mutilated cow near Barwon Heads and a mare at Little River. Likeliest explanation is that it came from a megafauna diprotodon, a giant wombat. The jury’s still out. Perhaps the wild man Buckley might have known.

It’s telling that a descendant of Buckley’s family, Jean Mayers, considers him more than just the ‘Go-Between Man’ he’s often remembered as. She says he’s the father of reconciliation. Some years ago, she tried to repatriate his remains from beneath a school playground at Hobart’s Battery Point to a ‘decent grave’ and memorial in Victoria.

She might not have been successful but a reconciliation memorial at Buckley Falls might be just the ticket. Might also help ease some of the tensions about that river race, too.

This article appeared in the Summer 2023 edition of Geelong + Surf Coast living magazine