Odd, the things that can come your way unexpectedly. A late aunt some years ago presented me a large envelope of unusual sketches and prints.

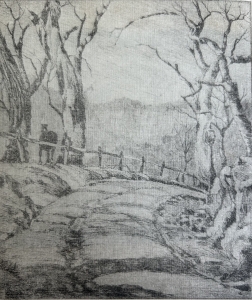

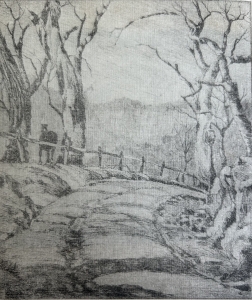

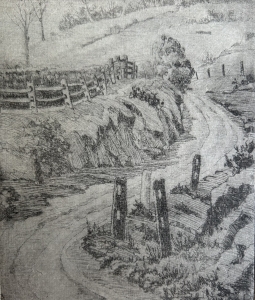

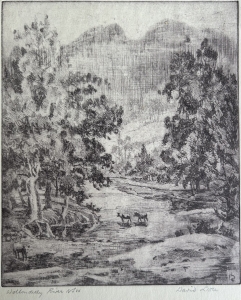

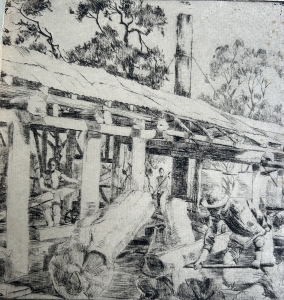

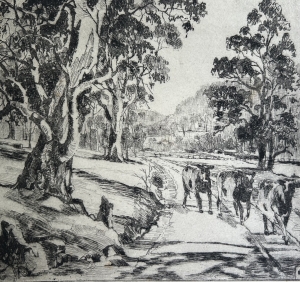

A swag of etchings and proofs of rural scenes in New South Wales. All rustic radiance, bucolic beauty and pastoral pulchritude if I can labour the alliterative allusions.

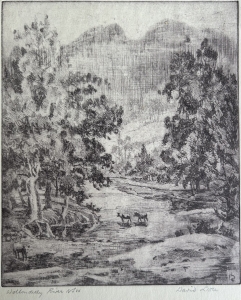

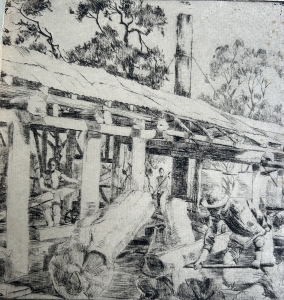

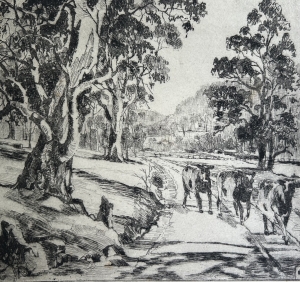

Lots of landscapes, mountains, eucalypts, post-and-rail fences, barns, stables, slab huts and farm buildings, cattle, horses, bushmen, timber bridges, bush tracks, gullies, rivers, creeks … a fair old Cook’s Tour of the Aussie bush, in fact.

Many of them depict scenes in and around the Burragorang Valley west of Sydney, where their artist, David Little, lived in the 1940s. Fair way, in the day, from Werribee where my grandfather, who supplied him with hard-to-source paper back in the wartime years, lived. Lot of the valley’s now underwater, flooded for Sydney’s Warragamba Dam in the 1950s.

David Little came out of Bacchus Marsh and Ballarat’s St Pat’s, same as my grandad, Leo Bartels. Both were born in 1893. Little’s old man, also a David, was a rate collector, hydraulic engineer and secretary across various local councils, Romsey, Bacchus Marsh, Melton and Werribee.

He lived in a Wattle Ave heritage home in Werribee I visited years later, as a kid, to hang out with a young schoolmate. By then, a scrap metal collection , with impressive aircraft fuselages and car bodies, had amassed at the rear of the property. A few years later, I recall 21st birthday and bucks turn parties.

Little the younger pursued a career in electrical engineering, earned himself a pilot’s licence in 1918, joined the Australian Flying Corps at age 25 and headed off to war only to have the Armistice signed while he was in transit. Took him a year to get home again whereon he settled in Sydney as a telephone engineer.

He’s listed on the Bacchus Marsh & District Roll of Honour and has a tree planted in his name in the town’s famed Avenue of Honour, not far from the old Woolpack Inn, one-time watering hole of the notorious bushranger Captain Moonlight with whom I share an odd connection (https://noelmurphy.com.au/portfolio-item/im-being-followed-by-a-moonlite-shadow/).

Little took off to the US and Canada in the 1920s, details are sketchy, returned to NSW where he married and moved about a bit – Armidale, Bondi, Burragorang and Avalon in a luxuriously furnished cottage among gum trees on a hill overlooking Pittwater. He worked in the public service and developed skills as a successful artist.

He suffered a nervous breakdown and while his artworks fetched impressive figures, one painting as much as 200 pounds in 1951, he described himself as an invalid pensioner. Well-educated, qualified and read – he was friends with the poet Paul Grano – his preferred art medium was oil but he produced a significant number of etchings as well.

A letter from my grandfather to Little, now in the University of Queensland’s Grano Collection, discusses everything from his paper supplies to Shakespeare, Grano himself – who was a St Pat’s old boy – and the nuns at Geelong’s Sacred Heart College, where my mother and her sisters boarded.

In his late 50s, however, Little’s life unravelled horrifically. He went to various doctors, including a Macquarie Street specialist, for mental problems. His wife, Ada, was diagnosed with a cancer which treatment was unable to contain. Her problems, however, deteriorated in catastrophic fashion.

As The Daily Telegraph reported on 19 August 1951:

“Detectives late yesterday charged a Sydney artist with having murdered his wife. They allege he killed her in their luxuriously furnished home at Taylor’s Point, Avalon.

“The dead woman was Mrs Ada Adeline Little, 52. David Little; 58, appeared at Manly Court, and was remanded until August 27.

“Detectives found Mrs Little’s body, battered about the head, in the living-room of her home.

“Little and his wife, who were childless, lived in a three-roomed cottage in Wandeen Road.

“The cottage, set amid high gum trees on a hill, overlooks Pittwater.

“Little, a successful portrait painter, bought the cottage six weeks ago.

“Neighbors said Mrs Little had a growth. They said that recent treatment had failed to stop the spread of the growth

“Early yesterday they saw Mrs Little collect the morning paper from the delivery van at the front of the cottage.

“About three hours later they saw a man leave the cottage and run down the road.

“Detective-Sergeant A. Garlick (Manly) found Mrs Little’s body.

“Dr H. Sanders, the local government medical officer, found Mrs Little had died from head and brain injuries about 8am.

“Many oil paintings were hung on the walls of the living room where the body was found. Most of the paintings were signed ‘David Little’. In the studio police found a half -finished portrait of an elderly woman.

“Neighbours said Little last week told them he had sold a painting in Avalon for £200.

“They told police that the Littles were a quiet couple.

“Little, grey-haired and stooped, appeared in Manly Court wearing a khaki wind jacket, grey trousers, and blue shirt.”

Three weeks later, Little was committed to stand trial for murder after the Coroner found Ada died from injuries feloniously and maliciously inflicted by her husband. Details that emerged in the coronial inquiry, as reported in the broadsheet Sydney Morning Herald, were class-A tabloid fodder.

“Francis Blackwell, retired, of Hudson’s Parade, Taylor’s Point, said that at 9.15 a.m. on August 18 he saw Little standing at the entrance of his (Blackwell’s) drive.

“Little, he stated, said to him: ‘Will you drive me to Newport, please? I have murdered my wife’.

“Blackwell said he led Little to a grass embankment near his house. Little appeared agitated and when questioned by Blackwell on the murder said: ‘I hit her with a mallet — I did it in cold blood’.

“At this stage, Blackwell said, Little was in a ‘terrible way and pulling up grass and muttering’.

“Little said to him: ‘They will hang me for this’.

“Detective-Sergeant Allen Garlick, of Manly police, said Little told him later that day that he had killed his wife and was prepared to take the consequences.

“Detective Garlick said he asked why he had killed his wife, and Little replied: ‘Well, it is a long story. A certain situation had built up in my mind concerning my wife and myself and something had to be done about it.

” ‘I had my breakfast. I got a mallet and I hit her four or five times on the head and killed her’. “

Little was duly sentenced to life imprisonment but on October 10 was taken from Long Bay Prison to Parramatta Mental Hospital where he died of natural causes on 29 November 1951.

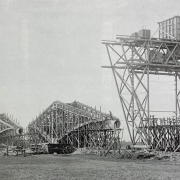

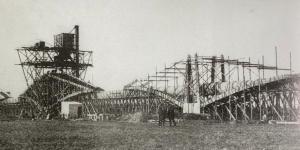

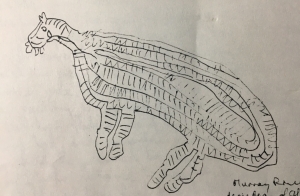

David Little and his one-time Burragorang home before being flooded.