The bull snorted and flicked his horns against a swarm of annoying flies as we inched out way around his rear and across a well-fertilised paddock toward a six-foot back fence we’d learned to hoik ourselves up and over in one smooth movement.

Hunched low, the three of us slipped behind the huge black Angus as surreptitiously as humanly possible. So we thought anyway. We’d seen enough episodes of Combat to fancy ourselves tyro commandos. We flanked him along the irrigation channel before making a run for it and hurtling ourselves at the grey timber fence.

We’d also learned to dodge cranky rams, snakes and swooping magpies. We knew how to shinny up trees of all sorts, knew what kind of silo grain would swallow you like quicksand and what wouldn’t.

We knew our way around swamps and cattails, knew edible mushies from deadly ones, birds and caterpillars and frogs. We could swing an axe with the deft alacrity of an adult, could fashion bows and arrows from willow, build rope tree-huts and knew how to tunnel deep down into a 10-metre haystack without killing ourselves.

In truth, the big black Angus had never shown the slightest interest in us but best be careful. You never really knew.

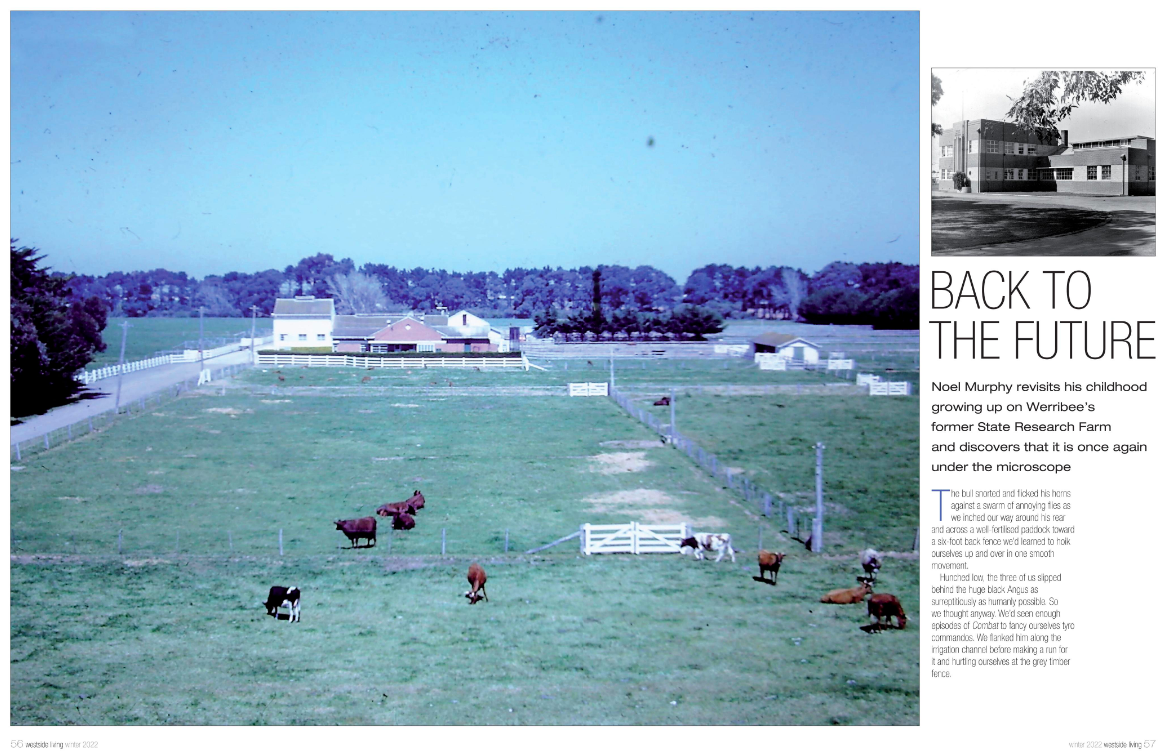

Our antennae were well-honed instruments growing up on Werribee’s former State Research Farm. Not without reason, on occasion, but for the main part this government-run agricultural research station was more an education playground than danger.

Cattle, sheep and poultry cackled and hoofed it alongside irrigation, crop and dairy experts, soil and animal husbandry researchers and technicians. Labourers, farmhands, tradies and administrators hoofed it alongside the scientists.

A small clutch of houses beside the farm’s H-shaped hub of sheds, labs and offices housed some two dozen families with another handful where the Werribee Police Station now stands. About a mile east of Werribee’s Watton Street centre, this little hamlet has been a quiet achiever with significant impact on farming that’s been felt around the world.

Today, however, the houses are all gone, the town’s population scattered and, until a study was announced recently, its social heritage seemed all but consigned to the dustbowl of Australia’s many forgotten histories.

Suddenly, it’s under the microscope in a ground-breaking new project to capture the social history of the State Research Farm, its people and its extraordinary achievements – all on film, in photography, memoirs and books.

The project will catalogue personal accounts by former SRF residents and workers, preserving the rich mix of life and work on the farm, which has been on State’s Heritage Register since 2001. The project is a collaboration between Dr Monika Schott and Arts Assist, with support from the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Region.

Monika, who recently completed a PhD and novel about Werribee’s historic Metropolitan Sewerage Farm, says the State Research Farm boasts a fascinating catalogue of stories and achievements which might otherwise be forgotten.

“There’s more than a century of intriguing goings-on that people don’t know about – war-time ergotine and opium projects, special efforts to help struggling farmers such as the Better Farming Train, experiments that resonated around the world,” she says.

“There was a social structure that had its own life while closely integrated with the nearby Werribee township’s businesses, schools, sports.

“Those people who worked and lived on the farm are now spread far and wide. The wealth of knowledge they possess about this remarkable institution is a heritage treasure yet to be seriously recorded in any fashion, even anecdotally. Without them and their families, we may not have things like powdered milk and flavoured yoghurt and myriad other things in our supermarkets today.”

The State Research Farm began in 1912, as the Central Research Farm. It swiftly developed a reputation for excellence with its experiments to improve cereals, grasses, soil, crops, irrigation, natural pastures, livestock, milk yield, plant nutrition and meteorological observations.

The SRF trained World War One veterans in the newest agricultural techniques with lectures and field demonstrations. By the 1920s, SRF scientists regularly took their findings to farmers around the State in various ways, including the Better Farming Train. The train influenced many farmers at the hundreds of stops it made. At one stage, nearly every grain of wheat coming out of Victoria had ancestors at the SRF – likewise, barley and linseed.

In World War Two, the farm produced vegetable seeds for local and international needs. It produced ergotine for shell shock and opium poppies to overcome the morphine shortage of the time. More than 300 women were trained through the Women’s Land Army in farming practices. University of Melbourne agriculture students spent their second year of course study on the farm.

The Research Farm hosted names such as Cameron, Richardson, Wilson, Raw, Bartels, Forster, Vasey and Wishart – people who brought an invaluable repository of knowledge to the farming sector.

“There are numerous other players, too: Morgan, Hewitt, Hodge, Sharkey, Banfield, Bartlett, North, Wiley, Dixon, Debrett, Mein, Pywell, Murphy, Pearson, Bagot, Bourke, Melican, Frith, Hussey, Gale, Ward, Fry, Leach, Robinson, Balshaw … and many, many more,” Monika says.

“Few of these people survive, however, many of their descendants do and they have powerful recollections of their SRF connections. Many have all manner of photographs and memorabilia tied closely to the farm and with little of this social history recorded, it’s vital to capture it before it’s lost forever.

“Such recollections will be of vital importance to the SRF’s heritage fabric, and that of Wyndham and Australia as well. Our work will not only assist in the conservation of the SRF’s heritage, it will provide a legacy of learnings into the belonging and social cohesion that exists within such communities, learnings that are vital for future sustainable urban development.”

The remaining old State Research Farm precinct has enormous potential to be repurposed as a creative, community, historical and tourism space and behind-the-scenes efforts are looking to bringing stakeholders together.

Who knows? Maybe one day they’ll be running courses on survival skills for country kids. I could tell them one thing: smoking cigarettes at the bottom of a haystack tunnel-hut’s not exactly the brightest thing to do …

Link: www.facebook.com/StateResearchFarmProject

This story appeared in the 2022 Winter edition of Westside Living