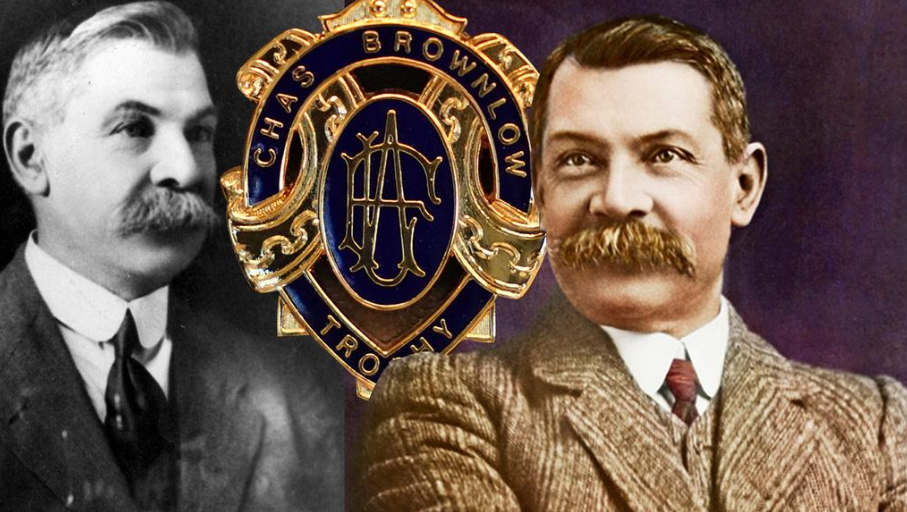

If they gave out prizes for walrus moustaches, he’d be a walk-up start for first prize with his formidable soup-strainer. History, however, remembers him for rather different, less hirsute, pursuits.

Charles Brownlow, namesake of the AFL’s fairest and best accolade, was a man of numerous abilities that for the past 100 years this year have been commemorated in the small blue and gold medallion bearing his moniker.

The Chas. Brownlow Trophy, as it’s correctly named, harks to an era from which much of Geelong’s leviathan bearing on the game of Aussie Rules has largely been forgotten, overlooked or shunned.

Even Charles Brownlow’s footballing performance itself is often glossed over, with medal/trophy references regularly focussing on his role as a football administrator rather than a Geelong Football Club star player, captain, and coach.

A fine administrator he was. No argument there. He was Geelong Football Club secretary from 1885 to 1923, president of the Victorian Football League in 1918 and 1919, and chairman of the Australian Football Council from 1919 to his death in 1924.

He had a founding role in the VFL and was instrumental in innovations such as boundary umpires, a timekeeping system, jumper numbers and the player tribunal.

But he was also a masterful on-ground protagonist of the game, right from the get-go.

“Geelong, in its days, has had many famous players. The names of the Wilsons, Billy Stiffe, Fairbairns, ‘Trusty’ Stevens, Ben Hall, the Cahills, Harry Steadman, Kerley, Barney Grecian, Jim Julien, and others, were names to conjure with,” the redoubtable footballer/cricketer/journalist Jack Worrall later recalled.

“But Charlie, when skipper of the senior team, stood alone as a tower of strength to his side, and as a born leader of men on the football field.”

In Brownlow’s early days as a teenage player, however, his father, “a disciplinarian of the old school”, looked askance at his footballing ambitions and threw up “stern parental objections”.

Worrall, again, takes up the story:

“Charlie … played under an assumed name, that of Green. His name always appeared on the team of players and in the papers under that alias.

“A great match was down for a certain Saturday, and excitement in ‘sleepy hollow’ ran high. The elder Brownlow was smitten by this excitement, and when Saturday afternoon arrived he wended his way to the Corio Cricket Ground to see the Geelong boys do battle with a crack team from Melbourne.

“The brilliant play of young Green more than attracted his attention, and in his enthusiasm he barracked for all he was worth for Green.

“His excitement greatly amused a friend of his who knew of the alias and when Brownlow pater went frantically wild over a bit of extra brilliant play on the part of Green, he slapped him on the back and facetiously asked Brownlow if he knew for whom he was barracking so splendidly.

” ‘Green, course,’ answered the excited father.

“ ‘No fear!’ said his friend, ‘don’t you know you are cheering your own son? Surely, after this you can’t forbid bid him to play senior football!’ ”

Brownlow’s father was gobsmacked but when Geelong won he raced to the dressing room to congratulate his son on a great game.

Brownlow was also a master craftsman, a silversmith, making trophies, watches and other works. He combined his business with more general services, including a china warehouse and a tobacco shop.

He made a great many medallions for sporting and community groups, and his works have featured in exhibitions at the Geelong Gallery.

Odd thing. The first recipient of the Brownlow medal, Carji Greeves, had similar issues getting on to the field. The Australian Dictionary of Biography relates that: “Geelong Football Club was keen to secure his services even before his schooldays were over, but the principal refused him permission to play.”

After he left school in May 1923, the club was on his case quick time, snapped him up and kick-started a celebrated career that saw him secure a Brownlow and three runner-up gongs, as well as two Cats premiership guernseys.

Greeves didn’t wear footy boots, preferring soft-leather ordinary boots, and bore a nickname drawn from the theatre character Carjillo, the Rajah of Bhong, for his swarthy skin colour.

He also travelled to the US to work as a kicking/marking coach with University of Southern California’s Trojans gridiron team. His name in turn lives on in the annual Cats’ best and fairest Carji Greeves Medal.

All up, a great ornament to a great ornament of the game. One thing Greeves doesn’t appear to have emulated, however, is Brownlow’s upper lip-holstery. If they do ever come up with a prize for one, I’d suggest Zach Tuohey might be another walk-up start.

This article appeared in the Geelong Advertiser 20 May 2024