Thursday August 12, 1852:Embarked at 11 o’clock in the “Aphrasia” steamer for Geelong. As she was pretty crowded with a precious lot of rough characters I took the saloon for it. It was a very stormy day and we had a head wind and were obliged to anchor in the bay all night …

Friday August 13: Landed at the wharf in Corio bay about 9 – went into the first eating house I met with and as it rained in torrents all day, I staid (sic) there to sleep.

Monday August 16: Strolled down to Corio bay and back to luncheon – the Barwon river runs at the back of the house and it is at present flooded and many of the houses in the banks under water.

NOT a lot of photographs of old Geelong back in 1852. Cameras were very rare, of course, which makes diarist-artists such as Edward Snell important figures in the city’s pioneering days.

Engineer/architect Snell’s journals provide an intriguing insight into everyday life of early Geelong, as well as its business goings-on and, in his case, a first-hand insight into his building of the Geelong-Melbourne railway line.

His artwork, while not hugely extensive and for the main part not a lot more than pencil sketches, still manages to reveal aspects of the fledgling town that more prominent artists of the era failed to document. He also predates many of them.

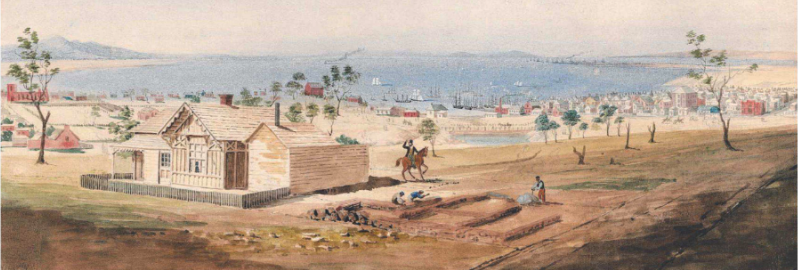

Geelong of Gold Rush era 1852 was growing rapidly and Snell was a vital part of that growth. His painting titled “Geelong in 1855” is as fascinating as Von Guerard’s better-known “View of Geelong” painted the following year.

While Von Guerard reveals much of the countryside from his vantage point at Highton’s Montpellier Park, Snell is much closer to town – beside the house he was building near the corner of Skene Street and Latrobe Terrace.

Johnstone Park is still a dam, known for its stinking animal carcasses, construction of St Paul’s Anglican church appears complete, adjoining railway buildings are well advanced, the port of Geelong is operating from both Point Henry with its small forest of ship masts and the present-day waterfront, and the township’s border appears abrupt at Gheringhap Street.

Eastern Park is a bare yellow open space. The town’s northern bay shores, which will one day host Geelong’s manufacturing precinct, are bare, as is the Bellarine Peninsula. Melbourne’s Dandenongs are visible on the horizon.

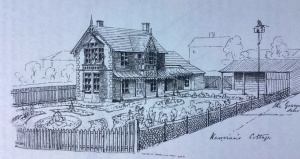

Snell’s house, or its foundations, is next to his partner, Ferdinand Kawerau’s home just a house-block back from Latrobe. It’s still there today, you’ll find a plaque on the Skene footpath out front.

Both houses appear well removed from anything else and there’s no actual sign of Latrobe Terrace at all. The township, by contrast, seems a busy, compact and densely populated area.

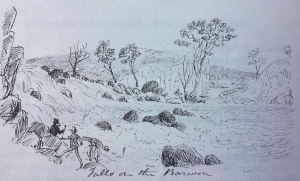

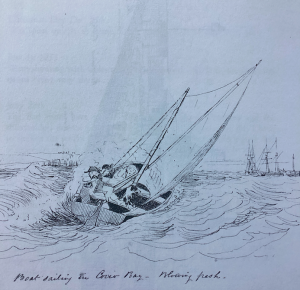

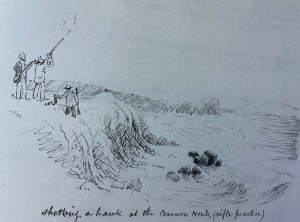

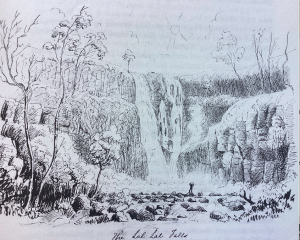

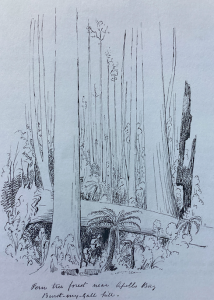

Snell’s diaries are peppered with sketches from his travels and a multitude of incidents along the course: sailing in brisk winds on Corio Bay, hopping from rock to rock at Buckley’s Falls on the Barwon, looking out over the Geelong waterfront from Limeburners Point, fern forests and a rudimentary pier at Apollo Bay, Lal Lal Falls, wild horse-carriage rides, shooting hawks at Barwon Heads …

His diary entries are short, snappy, engaging. His images too: A fisherman belting the daylights out of a mulloway with a boat paddle, Aborigines waving boomerangs at him, a leaking shack roof, a raucous wedding party crowd, boozy dance scenes, wailing babies, drinkers slashing whips about in a fly-infested cellar, camp clotheslines catching fire, shooting a horse, bogged carts, sleeping quarters crammed with snoring drunks, shooting parties, craw fishing, beach dunkings, a woman with a big nose, cooking naked in the rain, cutting hair for Aborigines …

Snell skewered caterwauling cats with knives through his wooden roof, drank himself fully parablotic, brawled and smoked, painted faces on the distended stomach of an Aboriginal boy, dug for gold, burned ant-beds, smashed bottles with stones when drunk and fought over finances with his business partner.

His wider artistic oeuvre includes sketches of waterfalls, coastlines, bush scenes, coaches, theatre performers and dancers, bridges, aborigines, burial sites, rivers, mountains, goldfields and diggers, rough camps and settlements, ships and ports. They’re remarkable.

His detailed and coloured sketches of snakes, dragonflies, centipedes, spiders, beetles, locusts, flies, bugs, grasshoppers, lizards, ants and other buzzing, biting or slithery creatures are equally intriguing.

Oh, the aforementioned Friday the 13th of Snell’s arrival in Geelong was every bit the miserable day that he posits, too.

“On Saturday morning, after an almost incessant rain of forty-eight hours, the Barwon attained a height nearly equal to the memorable 23rd May last, when the bridge at South Geelong washed away,” this newspaper reported on the following Monday.

“A considerable quantity of snow fell on the Anaki (sic) Hills and Station Peak, and was visible at the distance of twenty miles for several hours on Saturday. Such a severe winter as the present has not been before known in this part of Australia.”

Sorry to say it but looks like Snell dropped the ball. No pictures of snow on the You Yangs.

Might have put in a big one the night before.

This article appeared in the Geelong Advertiser 14 August 2023