VIVA ‘s Geelong Refinery stands testament to one of the most vital growth eras in Australian history — and yet it was almost mothballed before it even started.

The refinery, which ushered in powerful economic, social and ethnic changes during the post-war 1950s, was meant to be a bitumen and lubricants plant; not a petroleum refinery.

In fact, its proponents, the giant Shell group, knocked the initial idea on the head when it learned world market expectations for MVI lubricating oil had been seriously over-estimated.

Other factors, however, chiefly fears of oil-producing countries nationalising the industry — as had happened in Russia and Mexico, which seemed likely in new communist countries, and which Iran had tried to do on the Persian Gulf — gave the Geelong Refinery prospects new life.

Combined with government defence concerns, along with economic foreign exchange savings and job creation demands, the plant was revived. Ironically, it revived an earlier Shell refinery project that had been earmarked for Sumatra before war broke out in the Pacific.

Shell was anxious that Indonesia, too, was about to nationalise its oil industry. Two massive crude distillation units, abandoned on the Sumatran beach, were subsequently shipped to Geelong and one of Australia’s great post-war manufacturing projects set in train.

Like the Snowy Mountains hydro-electric scheme, the Geelong refinery drew heavily on labour from European migrants seeking new lives after the horrors and destruction of World War II.

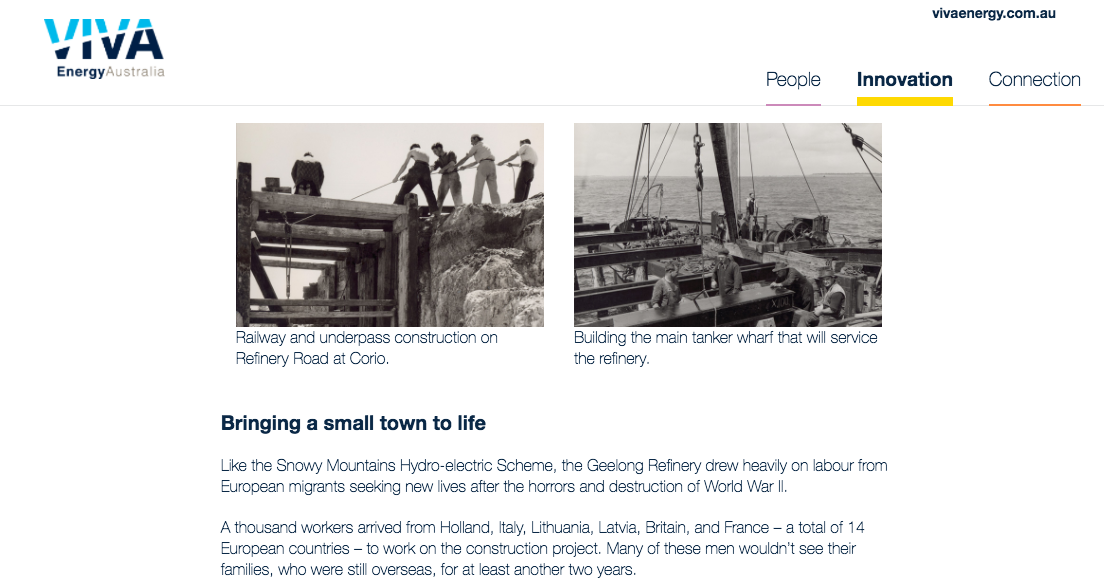

The 20 million-pound project that unfolded at Geelong’s Corio site — formerly a little-used paddock but with ready road, rail and sea access — was extraordinary.

Heavy lifting was the order of the day for three solid years from 1951 to opening day on 18 March 1954.

Construction saw the largest crane in the Southern Hemisphere, at 64.5 metres, on site, swinging 30-tonne sections into place. It saw the country’s longest oil pipeline built, stretching to Melbourne, going under rivers, capable of carrying 28,000 gallons every hour. It saw 200 ships bringing in project materials.

A thousand workers arrived from Holland, Italy, Lithuania, Latvia, Britain, France … some 14 European countries in all. Many of the men wouldn’t see their families, still overseas, for two years or longer. A massive hostel was built, 175,000 yards of earth was moved and a 90-acre housing scheme constructed — this became a new township, Norlane, named for the first Geelong casualty of World War II, Norman Lane.

The refinery’s all-important distillation unit, furnaces, boilerhouses, tanks, a wharf, pump stations, warehouses, offices and workshops were all built. The project was enormous, an economic and social game-changer.

Migrants’ lives were rebuilt, their hopes and ambitions revived. Geelong’s social fabric was indelibly refashioned and its economic prosperity, along with that of Victoria and Australia, underwritten with a rock-solid, reconfigured wealth-producing industry that was now more assured, more secure from the vicissitudes of foreign politics.

More than 60 years on, the Viva refinery at Geelong today remains a vital contributor to Australia’s energy needs, an important foreign exchange earner and a key employer.

Its green credentials are bolstered by ongoing environmental initiatives. It remains an strong ongoing contributor to the community. It maintains also a weather eye to opportunities the future might hold for its endeavours and its broad family of employees.

For a refinery that almost failed to get off the ground, it is a remarkable testament to determination and diligence, to confidence and community, and to constant positive planning and achievement.

In short, it’s testament to living, or in the Romance languages — Viva.