Postcards from the heartland …

Long-standing joke in my family is that the many French letters my grandmother was sent by her Gallic aunt a century ago were addressed to her at ‘Truganina Loose Bag’.

Pretty cruel, really. She was a darling thing. Widowed at 47 with eight kids, she drew on country girl nous garnered on the rocky windswept plains of Truganina and Tarneit to get through. And did so admirably.

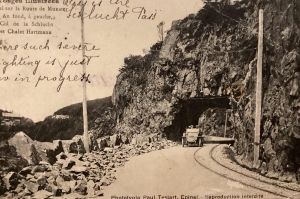

The letters were actually postcards – of rivers, mountains, snowy forests, buildings, bridges, farms – most of them out of old France, the Vosges, the Alsace, more than a century ago, many of them during the Great War. Shots of soldiers at the Pyramids, in the trenches or on the march are peppered through the collection. One shows a road where her great grandmother was stalked by wolves.

Sad story. Granny’s aunt, sister of her dad, came out to Oz in 1873 with their parents, fleeing Strasbourg in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian war. The aunt was sent home to her grandmother after a couple of years in an orphanage when her mother died of TB months after her arrival. Her brothers were sent up country to friends. Her dad remarried.

.

.

Been scouring through the postcards looking for info that might help inform a neat project going on in what’s officially Tarneit but what we always called Truganina: Granny’s old 1877 bluestone home, burnt out in the 1969 fires that ravaged the area, is being rebuilt.

All by the City of Wyndham. Costing a small bomb but looks quite remarkable. Heritage restoration building works have taken place already to secure the building’s structural integrity and renders are up online showing café plans for its future. All very smart looking and positioned as it is, beside a large park and plenty of homes, it’s already attracting interest from potential operators.

Place is called Remiremont. It was built by William Doherty in 1877, bought and farmed by my great grand-pere Louis Valentine Paul Didier in 1903 and named for his French home, and stayed in the family with his son Paul until 1956.

LV Paul Didier’s sister Jeanne’s postcards were sent regularly and broach harvests, seasons, music and birthdays but assume a more sober tone with the onset of war; the carte postale images changing from bucolic landscapes to ambulance wagons, bombsites, military parades and uniforms, battle scenes, bombings and wounded soldiers.

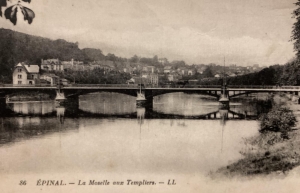

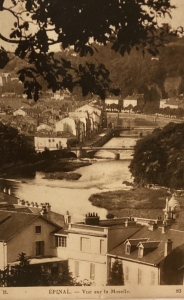

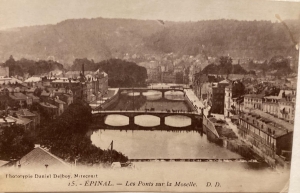

Jeanne was a single girl, an English and German teacher, living in Epinal, on the Moselle River, in rural France’s Vosges mountains about 20km from Remiremont. The area pops up occasionally in coverage of the Tour de France.

While she was boning up on her linguistics skills with the correspondence, the cards were pored over at Remiremont, Tarneit, by her young nieces; their exotic European allure a captivating, all-but-unreachable destination – as much as Australia was to their author who penned a raft of letters as well. Both towns became bywords for the family’s sense of history.

Tourist guide books don’t give a great deal away about Epinal. Some go as far as to advise against going there. Don’t heed what they say. You might even thank them. If anything, they’re protecting the charm of this provincial capital on the edge of the Vosges Mountains.

Epinal straddles the Moselle River, a little off the tourist beaten track and about 85 km southwest of the Alsace’s famous city Strasbourg. The only reason this scribe ventured anywhere near it was to investigate the home of this long-dead relative who sent the often poignant postcards to Australia.

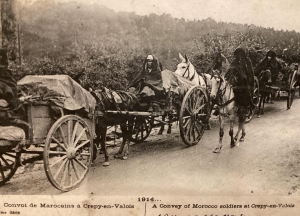

The cards, hundreds of them, were a source of mystery and deep fascination. The images of these cards varied greatly. A great many were military, most of the others tourism- oriented – all of them might be considered historical documents. There are soldiers squatting in trenches, exhausted Moroccans returning from the front, helmeted guards with rifles at hand watching over vital railway lines, army vehicles negotiating dangerous mountain paths, memorials to the fallen.

Then there are buildings, idyllic mountain scenes, stone fords, parks, fountains, the Moselle in flood, dour-looking family groups, churches , streetscapes, houses set on hillsides. And virtually all of these in a faraway romantic monochrome haze – one that seems to even soften the harsh image of German prisoners of war being marched through town. In return for all these, great grand-pere sent Australian newspapers back to his sister to use in her job as an English teacher.

The mutual correspondence went on for decades, all of which made Epinal, for this scribbler, a place of great curiosity. Remarkably, visiting the town from getting on to a century’s distance not much had changed. The parks, memorials, bridges, churches, buildings, are largely still in place. The town square has changed little and the Moselle still flows through the heart of town.

What was surprising to learn was the town history. Its foundation dates back to a 10th century monastery built by the Bishop of Metz. The town soon became a political, economic and cultural centre at the crossroads of four nations: Lorraine, Alsace, Burgundy and Champagne. In the 18th and 19th centuries, it developed a reputation as the world capital of popular print-making, an industry which still flourishes to this day in a working museum-gallery, the Imagerie.

Epinal claims to be the most wooded town in France, with the forest galore, and it is a Mecca for hiking, horse-riding, mountain-biking, camping, sailing and fishing. It boasts numerous festivals – street theatre, comic theatre, music and international piano competitions – plus art houses and museums, flower arrangements everywhere and of course all the charm of its many centuries-old townhouses, churches and provincial architecture.

With any luck, Epinal’s charms will remain intact for some time yet, especially if the guidebooks continue to recommend against visiting.