PENANG, 28 October, 1914: It was damned sneaky. You have to give that much to Captain Karl von Muller for his early morning assault on the Russian cruiser Zhemchug.

But right in front of guests at Penang’s finest hotel, the E&O Hotel, including the Zhemtchug’s captain, Baron Cherkasov and his wife Baroness Varvara?

Now that’s downright bloody impudence. Even if it was the Great War.

It’s odd how you can almost hear the old white-whiskered generals huff-huffing in their gin and tonics. All mutton chops, pith helmets, God Save the Queen and ‘curse this damn heat’ from their rattan lounge chairs.

That’s the pervasive British colonial ambience of the Eastern and Oriental Hotel in Penang’s George Town, though.

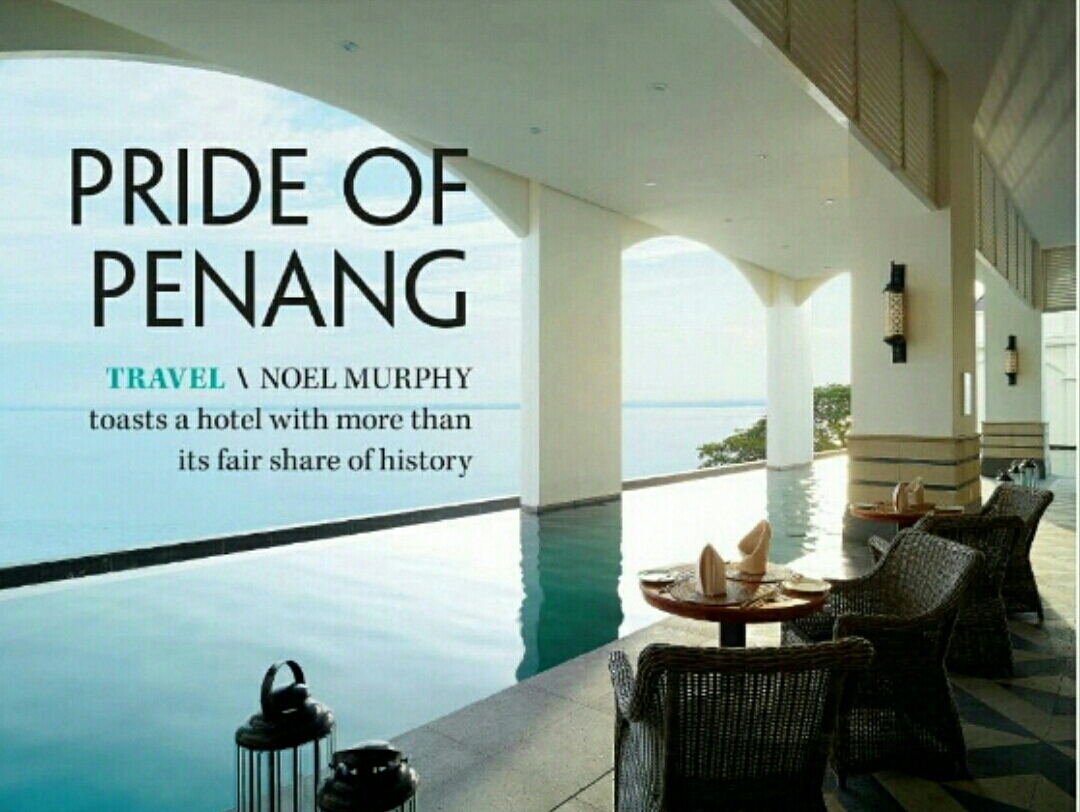

Punkah fans and cigars, canon and bougainvillea on the lawn, high tea and parquetry inside. Verandahs and palms, blazing white facades, plantation windows with glass enough for half of Christendom, teak furniture and darkly elegant, brooding jungle bars and lounges.

Another cucumber sandwich if you would you please, Crichton. I wonder what the natives are doing, what? Damn, I wonder how that German von Muller and his Emden tricked their way into the bay to sink that Russian.

Yeah, well, maybe once upon a time …

These days, the E&O is testament to painstaking architectural restoration, exquisitely-mannered service and first-order cuisine as much as it might be to any extant species of old-world colonialism.

Penang, as Great Britain’s first major foothold in the Far East and for many years its busiest trading port there, holds an important place in history.

Its architecture alone, a chaotic mix of Malay, Chinese, Indian and British, has made all of George Town UNESCO heritage listed. Pull down an old building and you lose title to it.

If George Town has a single architectural icon, and really it has many large and small, the popular winner must be the E&O.

It’s hands-down the city’s flashest hotel; an opulent six-star establishment with safari-helmeted doormen, tuxedoed bellboys and walls dripping with the kind of history only guest-lists with names such as Kipling, Conrad, Chaplin, Coward, Hesse, Fairbanks, Pickford, Sun Yat-Sen can conjure.

It’s the perfect tipping off point for exploring Penang’s treasures; natural, historical, architectural, culinary _ the tolerance of the Muslim, Hindu and Christian societies that co-exist in Penang is instructive in more ways than one.

The culinary kaleidoscope, however, is magnetic and the exotic Asian fare on offer is mouth-watering. Think laksa, mee goreng, taukua rendang, fried oyster, tom yam mee, char hor fun … and, of course, a cooling Tiger beer in your tank to soak up the heat.

But the E&O offers its own species of exquisite and international dishes, too, along with the high teas naturally and, to this correspondent’s delight, first-order service from the darkly timbered Farquhar’s Bar to poolside and its palms _ from which you can cast a martial eye over the watery terrain where Captain Karl blasted old Cherkasov’s craft to smithereens.

This beautiful old hotel has weathered numerous upgrades and extensions, and depredations in its low times. But it still lilts melodically to a world of colonial cricket and pavilions, turf clubs and buffets, white suits, parasols and jinrickshas.

Authors Khoo Salma Nassution and Malcolm Wade, in their sumptuous Penang Postcard Collection coffee table offering, detail a little of the hotel’s provenance:

Armenian brothers Martin and Tigran Sarkies opened the Eastern Hotel in 1884 and the Oriental Hotel the following year. They extended their operations to the Raffles Hotel in Singapore in 1887 and then The Strand in Rangoon. A third brother, Arshak, entered the fray in 1891. They were nothing if not entrepreneurial.

Extensions were carried out by architect Henry Alfred Neubronner between 1902 and 1911, starting with a series of connected bungalow and adding wings and annexes to make the longest sea front of any hotel in Asia.

What was in 1890 a hotel with 30 bedrooms and a hall with a dozen dining tables and an “oasis of civilisation’’ by 1939 was a “magnificent hotel, with large and palatial suites, with telephones in every bedroom, and the rare luxury in the East, constant hot and cold running water in English baths’’. It also boasted rich carpets, a tremendous dome and a large permanent orchestra.

These days, the E&O is considered six-star but as the manager informs me it’s still an old hotel requiring constant maintenance. Which explained the racket coming from the Rudyard Kipling suite down the hall. Waterproofing works.

By way of apology, he moves me to a new suite; an expansive twin-room affair with huge tiled bathroom, dark wooden floors, wardrobes and tables, side tables, cabinets, plantation doors, thick carpets, candlelabra-like lanterns, double TVs, wi-fi, butler buttons, botanical paintings, geometric panelling, giant green fronds peeping in at every window.

It’s a happy blend of old and new but I soon repair to the shady retreat of Farquhar’s watering hole downstairs to ruminate about posh jungle bars and this particular one’s low-slung rattan and timber club chairs, its art deco and Chinese barmen in 1960s James Bond suits _ and the linen-suited Hemingway lookalikes in its dark corners brooding over their olives and cashews.