Tarneit’s Sayers Road, home to Villawood Properties’ Alamora, was Nissen huts, quail-shooting, roadside eucalypts, wire fences and little else a few years back. Different now.

Mount Cottrell was to the north, beyond Cowie’s Hill and its brace of MMBW water tanks. The Spring Plains swimming hole was to the west across the Werribee River carving its way across the plains from Korweinguboora up near Daylesford down to Port Phillip.

The river was choked with fallen trunks, victims of what locals knew to be Victoria’s fastest river when in flood. The same wisdom contended that Bungee’s Hole, downstream in Werribee proper, was bottomless.

Sayers Road was designer-made for my rock bandmates as we happily plied our Santana and Doobie Brothers decibels across the wide-open spaces, rousing approbation from nothing more than the local mudlarks offended by thundering old valve amps. Raucous parties upset no-one.

Tarneit and its neighbouring Truganina were tough, rocky, grazing runs. Well out of town and aligned with Melton as much as Werribee, what little community infrastructure there once was was long gone even then – the old Trug township, post offices, old timber houses and bluestone homesteads, the odd hall and even school.

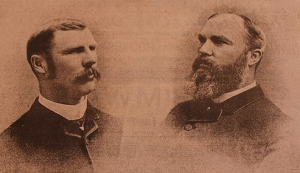

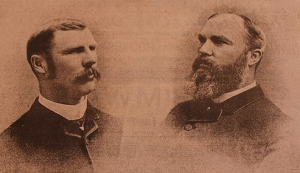

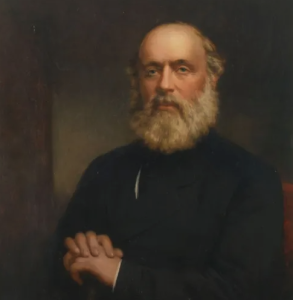

Remiremont Chaffey brothers George and William

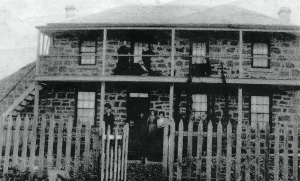

Some ruins remained, and still do, my ancestral home ‘Remiremont’ for one – a bluestone double-storey pared back to one for safety reasons but burned out in the 1969 fires. My grandmother grew up there, my mum stayed there with her uncle/aunty in the 1930s and ’40s and travelled to church not in Werribee or Melton but Yarraville.

For kids back in the late ‘60s, early ‘70s, Werribee stopped at Shaws Road. Tarneit was somewhere out on the dusty Never-Never. But we rode out to explore the farmyards behind the CSIRO and the cemetery along Railway Avenue. Long before Glen Orden/Birdsville or Werribee Plaza existed, let alone Orchard Place, the first of Villawood Properties’ many Wyndham communities.

Cobbledicks Ford Tarneit Primary School

We pedalled all the way out through Tarneit to Cobbledicks Ford, a hard trundle up Derrimut to Dohertys Road then down Dukelows and a precipitous grassy hill to the river. You could make out the Eynesbury stand of endangered grey box eucalypts across the river from the top of Dukelows. The Eynesbury old station’s since been transformed into an urban outpost south of Melton, south of Melton South and finally south of Exford. Urban sprawl will catch it soon enough.

But while Tarneit and Trug seemed no-man’s land, there are old and familiar names tied to it – Chirnside, Shanahan, Hogan, Leake, Campbell, Davis, Lee, Lawler – and there’s a history.

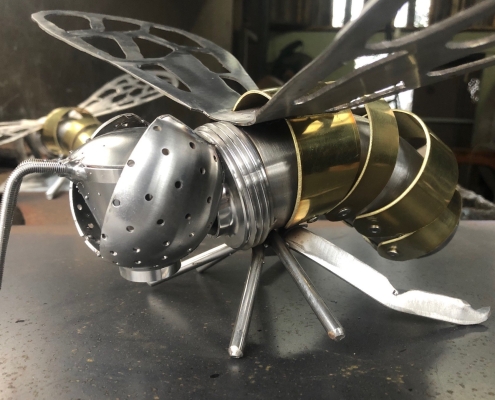

For one, there’s the 1888 Chaffey’s Channel culvert, pump, sluice gate – west of Sewells Road and thought to be to be the first irrigation scheme built in the area and the first crack at the game by the pioneering Chaffey Brothers. Didn’t fly, however, due to pumping and servicing problems and was moved to the Glen Devon Stud and what is now the Riverbend Historical Park.

The North Base Stone at 1245 Sayers Road is of State significance. It was laid in the 1860s by the Geodetic Survey of Victoria to facilitate the survey process used to subdivide land during the early days Victoria. Not much to look at but swags of map would be shot without it.

Wattle Park on nearby Sewell’s Road, was owned by the Chirnsides and leased to tenant farmers. The Chaffeys efforts ran through it.

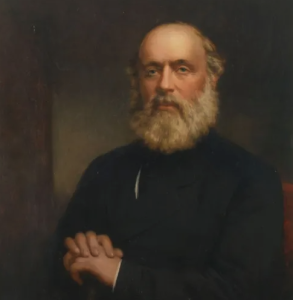

John Batman Andrew Chirnside

The Werribee River’s been important forever, of course, as border, water and food source for Aboriginal clans of three language groups – the Marpeang bulluk, Kurung jang balluk and Yalukit willam. As a young Werribee reporter I recall covering Indigenous remains unearthed along the river by a mining operator.

In the late 1830s and 1840s, the Werribee River was the scene of conflict between Aborigines and the European colonisers. The squatter Charles Franks and a shepherd were speared to death near Mount Cottrell in July 1836. This resulted in the Mount Cottrell massacre – a punitive party led by John Batman which came upon a large party of Aborigines and indiscriminately shot and killed at least 10. There are accounts of arsenic laced flour being given to local aborigines.

Today, the river waters the Werribee South market gardens, is popular with anglers and bushwalkers and provides a rich flora and fauna habitat.

Alamora’s part in the reshaping of Sayers Road draws people to an area where its background is little known and little appreciated but where it remains a vital player in the lives of its residents in terms of location, geography, environment and natural resources.

- Noel Murphy is Villawood Properties’ PR & communications manager