Otways timber cutter Murray Kidman is a rare breed, perhaps even endangered … NOEL MURPHY explains

The darkest depths of the Otway ranges can be a mysterious part of the world: a secret bastion of panthers and hermits, tiger quolls and carnivorous snails, strange subterranean rumblings, exquisite waterfalls, giant ferns, ancient trees.

Oral tradition tells of Aborigines dealings and voracious sealers, of bitter clashes with early settlers. Manufactured lore says the Big Kahuna, a machine designed in the 1950s to create monster swells around Lorne, is in storage somewhere in the Otways, maybe an old hayshed or somesuch.

The Otways and the southwest is renowned for UFOs, quicksand and floating islands to shipwrecks, dinosaurs and megafauna trails. Dig further and you’ll find stories of spontaneous combustion, ghosts, Rudyard Kipling, bush cathedrals, wartime German submarines …

One thing not so well known about the Otways, however, has a charming musical reference. Quietly, over the past 30 years, they’ve developed a reputation for fine musical instrument timbers — specifically for its stock of blackwood. They’re seized on hungrily by luthiers for the backs, sides, tops, headstock veneers and necks of acoustic guitars.

Blackwood is used also in the necks and body of electric guitars. It’s put to further use in mandolins, mandocellos, bouzoukis, ukuleles. Talk to any musician with a hand-made instrument and you’ll hear of spruce, mahogany, maple, ebony, rosewood — and blackwood.

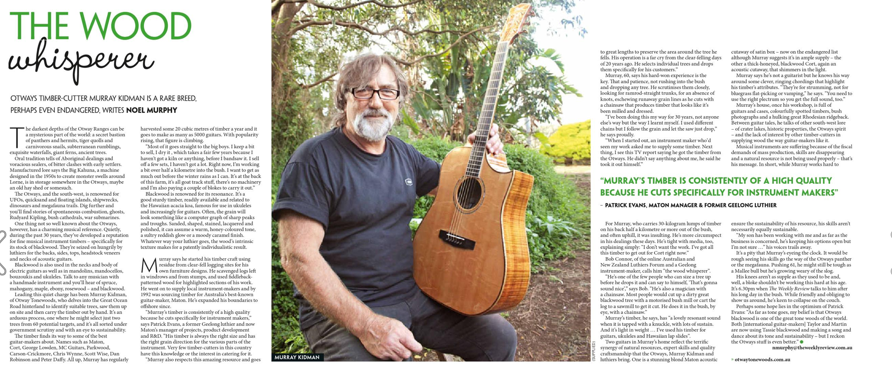

Leading this quiet charge has been Murray Kidman, of Otway Tonewoods, who delves into the Great Ocean Road hinterland to identify suitable trees, saw them up on site and then carry the timber out by hand. It’s an arduous process, one where he might select just two trees from 60 potential targets, and it’s all sorted under government scrutiny and with an eye to sustainability.

The timber finds its way to some of the best guitar-makers about. Names such as Maton, Cort, George Lowden, MC Guitars, Parkwood, Carson-Crickmore, Chriss Wynne, Scott Wyse, Dan Robinson and Peter Daffy. All up, Kidman has regularly harvested some 20 cubic metres of timber a year, which goes to make as many as 5000 guitars. With popularity rising, that figure is climbing.

“Most of it goes straight to the big boys,” Kidman says. “I keep a bit to sell, I dry it , which takes a fair few years because I haven’t got a kiln or anything, before I bandsaw it. I sell off a few sets, I haven’t got a lot.

“Right now, I’m working a bit over half a kilometre into the bush. I want to get as much out before the winter rains as I can. It’s at the back of this farm, it’s all goat track stuff, there’s no machinery and I’m paying a couple a blokes to carry it out.”

Blackwood is renowned for its resonance. It’s a good sturdy timber and readily available, and related to the Hawaiian acacia, koa, famous for ukuleles and increasingly for guitars. Often, the grain will look something like a computer graph of sharp peaks and troughs.

Sanded, shaped, stained, lacquered and polished, it can assume a warm, honey-coloured tone, a sultry reddish glow or a moody caramel finish. Whatever way your luthier goes, the wood’s intrinsic texture makes for a patently individualistic result.

Kidman says he started his timber craft using residue from clearfell logging sites for his own furniture designs. He scavenged logs left in windrows and from stumps and used fiddleback-patterned wood for highlighted sections of his work. He went on to supply local instrument makers and by 1992 was sourcing timber for Australia’s best known guitar-maker, Maton. He’s expanded his boundaries to offshore since.

“Murray’s timber is consistently of a high quality because he cuts specifically for instrument-makers,” says Patrick Evans, a former Geelong luthier and now Maton’s manager of projects, product development and R&D.

“His timber is always the right size and has the right grain direction for the various parts of the instrument. Very few timber cutters in this country have this knowledge or the interest in catering for it.

“Murray also respects this amazing resource and goes to great lengths to preserve the area around the tree he fells. His operation is a far cry from the clear-felling days of 20 years ago. He selects individual trees and drops them specifically for his customers.”

Kidman, at 60, says his hard-won experience is the key. That and patience, not rushing into the bush and dropping any tree. He scrutinises them closely, looking for ramrod straight trunks, for an absence of knots, eschewing runaway grain lines as he cuts with a chainsaw that produces timber that looks like it’s been milled and dressed.

“I’ve been doing this my way for 30 years, not anyone else’s way but the way I learned myself. I used different chains but I follow the grain and let the saw just drop,” he says proudly.

“When I started out, an instrument maker who’d seen my work, asked me to supply some timber. Next thing, I see this TV report saying he got the timber from the Otways. He didn’t say anything about me, he said he took it out himself.”

For Kidman, who works like a navvy, humping 30kg lumps of timber half a mile or maybe further out of the bush on his back, and often uphill, it was insulting. He’s more circumspect in his dealings these days. He’s tight with media, too, explaining simply: “I don’t want the work. I’ve got all this timber to get out for Cort right now.”

Bob Connor, of the online Australian and New Zealand Luthiers Forum, and another Geelong instrument-maker too, describes Kidman as “the wood whisperer”.

“I think he’s one of the few people that can size a tree up before he drops it and can say to himself ‘That’s gonna sound nice’,” says Connor.

“He’s also a magician with a chainsaw. Most people would cut up a dirty great blackwood tree with a motorised bush mill or cart the log to a sawmill to get it cut. He does it in the bush, by eye, with a chainsaw.”

Kidman’s timber, he says, has “a lovely resonant sound when it is tapped with a knuckle with lots of sustain. And it’s light in weight … I’ve used his timber for guitars, ukuleles and Hawaiian lap slides”.

Two guitars in the Kidman home reflect the terrific synergy of natural resources, expert skills and quality craftsmanship that the Otways, Murray Kidman and luthiers bring. One is a stunning blond Maton acoustic cutaway of satin box — now on the endangered list although Murray suggests it’s in ample supply — the other a thick-honeyed, blackwood Cort, again an acoustic cutaway, that fairly glistens and shimmers in the light.

Kidman says he’s not a guitarist, but he knows his way around some clever, ringing chordings that highlight his timber’s attributes.

“They’re for strumming, not for bluegrass flatpicking or vamping,” he says. “You need to use the right plectrum so you get the full sound, too. I’ll use some open tunings but generally normal tuning.”

His house, once his workshop, is a man-cave cum residence populated by guitars and cases, colourfullys spotted timbers, bush photographs and a hulking great Rhodesian ridgeback. Between guitar tales, he talks of other southwest lore — of a crashed Wirraway in Lake Corangamite and muddy would-be looters, of onions and crater lakes, historic properties, the Otways spirit — and the lack of interest by other timber cutters in supplying wood the way guitar-makers like it.

Musical instruments are suffering to the fiscal demands of mass production, skills are disappearing and a natural resource is not being utilised properly is his message. In short, while Kidman works hard to ensure the sustainability of his resource, his skills aren’t necessarily equally sustainable.

“My son has been working with me and as far as the business is concerned he’s keeping his options open but I’m not sure …” his voices trails away.

It’s a pity that Kidman’s eyeing the clock. It would be rough seeing his skills go the way of the Otways panther or the megafauna. Pushing 61, he might still be tough as a Mallee bull but he’s growing weary of the slog.

His knees aren’t as supple as they used to be and, well, a bloke shouldn’t be working this hard at his age. It’s 6.30pm when TWR talks to him after a long day in the bush in high 30s temperatures. While friendly and obliging to show us around, he’s keen to collapse on the nearest couch.

Perhaps some hope lies in the optimism of Pat Evans: “As far as tone goes, my belief is that Otways blackwood is one of the great tone woods of the world. Both (international guitar-makers) Taylor and Martin are now using Tassie blackwood and making a song and dance about its tone and sustainability — but I reckon the Otways stuff is even better.”