You might have noticed a great private collection of historical Australiana owned by Trevor Kennedy headed the National Museum’s way, half sold, half donated.

Loads of interesting stuff in it. Colonial clocks and couches, paintings and porcelains, jewellery galore, a stuffed kookaburra fan, a diamond brooch Charles Kingsford Smith presented his wife, Lionel Rose’s bantamweight world championship trophy … 5000 items all up.

Kennedy’s a former editor of an old Aussie fixture himself, The Bulletin – or The Bushman’s Bible as it was known. For years, it was the bastion of the country’s greatest writers.

Political, pejorative and poetic, artistic and amusing, in its heyday, its old school traditions wouldn’t last long in today’s PC world. Like many other mastheads, old and contemporary, it’s gone to Gawd, as its Strine scribblers might have averred.

This week will see the art prize named for The Bulletin’s founding editor, J.F. Archibald, awarded from a record crop of 1068 entries. As usual, the entries range from weird to wonderful.

Like many things Bulletin-related, it’s attracting its usual controversy. One critic last week slammed the prize as a show of freaks and fakes for a visually-illiterate audience. And there’s no doubt been a few fakes and horrors down the years.

And fair old shitfights, too, if you’ll excuse the French: Charcoal images, caricatures, paintings from photos rather than life, William Dargie’s long winning streak, the Bananas in Pyjamas exclusion …

But if you want to look for prevaricators, you can’t ignore the Geelong-born Archibald himself. He arrived John Feltham Archibald on January 14, 1856, in the former suburb of Kildare’s police residence to one Charlotte Jane Madden. His old man was Irish copper Joseph Archibald. You’ll find a memorial at the corner of Weddell and Church, beside West Oval.

Archibald moved about – Warrnambool, Ballarat, Port Fairy. He told Bulletin business manager William McLeod he was born in Warrnambool. Oddly, he didn’t live in Adelaide, where his 1919 death certificate says he was born.

His name moved about too: John Feltham, John Francis, Jules Francois and Julian. He strongly preferred the French affectation in his later years. Archibald also claimed his mother was of Jewish-French extraction. And when he married Rose Frankenstein in 1885, the marriage certificate had his birthplace as France.

No-one’s too sure why the strange French predilection. It might have been to impress an actress, maybe some ties he had to a French family in Melbourne. I can’t talk, I suppose. I’ve been saying I’m more French than Irish for years. But my maternal forbears came out of Denmark and Strasbourg, which is German half the time, and the Vosges. At least some of them spoke French.

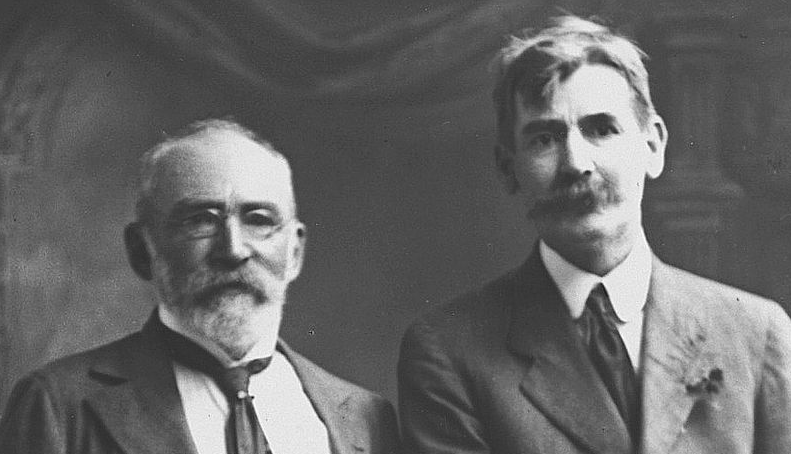

For all his manufactured Francophile peculiarities, Archibald was revered for his Bulletin roll call of literary and artistic giants, such as Henry Lawson, Tom Collins, Steele Rudd, Banjo Paterson and Miles Franklin.

Norman Lindsay, chief family figure in the so-called ‘Plague of Lindsays’ whose libertine artistic expressions both shocked and delighted the country, recalled Archibald graciously back in the mid-1960s:

“It is hard at this date to convey the almost esoteric reverence with which Archie and The Bulletin were regarded in those days.

“The Bulletin … had startled into being a genuine urge of nationalism. It maintained a high standard of prose and poetry, and black-and-white art was getting in its pages a first chance of individual expression.

“Over all that loomed the mysterious figure of Archibald, sardonic, benevolent, ruthless, encouraging, a final arbiter of values, an omnipotent maker or breaker of reputations.”

So peculiar stuff, all round, our Archibald. Not unlike former editor Kennedy, in his way, who by turns sidled up alongside more contemporary media moguls such as Packer, bankers such as Turnbull, financial advisors such as Rivkin – and all sorts of hot water courtesy the Offset Alpine Affair.

One of the most interesting items in his Australiana collection is a silver collar that was presented to a publican’s dog in 1834 for killing 20 rats in the astonishing time of two minutes and two seconds.

That’s bloody impressive by any metric. And if there was gold prize for art imitating life you reckon it’d be right up there – although I don’t know if our Francophile would agree. Might be just a bit too quelle horreur.

This article appeared in the Geelong Advertiser 22 September 2020