A meteoric struggle of wills

Two brash colonial scientists jostle for possession of an astonishing 19th-century astronomical discovery just outside Melbourne – the world’s largest iron meteorite.

This prodigious cosmic lump of metal is a glittering prize but at stake also are critical notions of heritage ownership in an era of nascent cultural awareness.

Author Sean Murphy’s The Cranbourne Meteorite is a long-forgotten story of Victorian scientists fighting to assert their authority and challenging hide-bound imperial assumptions of ownership and a gloves-off brawl it is, indeed.

They might have been living in the wealthiest gold province of Britain’s 19th-century empire but these scientific leaders found themselves fairly flustered not by any auriferous anomalies as much as a ferrous phenomenon.

The Cranbourne Meteorite details the mini-culture war fought over this highly-sought nugget of iron, and the relationships, personal and professional, wrought in its wake.

Murphy lives at Berwick, close to where the meteorite struck earth. His account is an effort to highlight Cranbourne’s alien visitor, the nature of meteorites and asteroids as well as Australia’s impact craters.

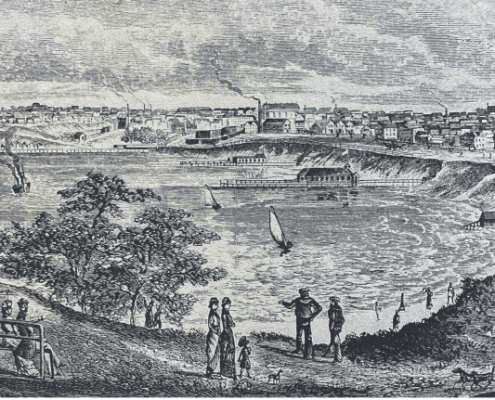

He reveals the scrapping over the meteorite’s ownership in the colonial milieu where his protagonists lived and worked. He relates his meteor’s milestones with a weather eye on the growth of Melbourne and its science and academia at the same time.

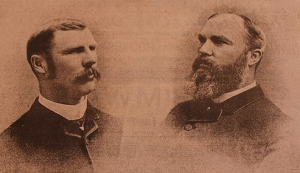

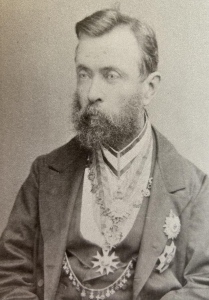

Frederick McCoy (left) and Ferdinand Mueller.

“It’s a local event with astronomical fireworks and strong personalities,” he says. “The leaders of these institutions were deeply invested in attempts to retain, or remove, the main meteorite fragment: a 3.5 tonne monster named Cranbourne No. 1.

“This arm-wrestle is largely conducted via letters, a very many letters, and in the chambers of learned societies such as the Royal Society of Victoria.”

Murphy exposes professional jealousies and how two pioneering Victorian scientists, Irishman Frederick McCoy and German-born Ferdinand Mueller, held determined but divergent views on what to do with the No. 1 specimen. Two iron wills competing for one iron meteorite, you could say.

“Cranbourne was, for a time, the largest iron meteorite in the world,” says Murphy. “And it has a colourful cousin, the Murchison meteorite, which fell on the Goulburn River township in 1969.

“Murchison’s peculiar chemistry made it a much-studied specimen and famous the world over, so Victoria has two famous contributions to Australia’s meteoritic honour-roll.”

The Cranbourne Meteorite

By Sean Murphy

Australian Scholarly Publishing, $49.95