Train wreck: the old ’73 comes to grief

North Geelong, August, 1873: TALK about bursting your boiler. This is what happens when a train’s means of power and propulsion, the boiler, breaches its pressure co-efficient.

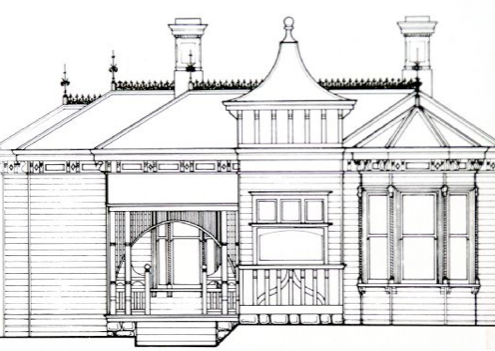

A goods train bound for Ballarat was passing the Telegraph Bridge at what was then called Kildare at 11 in the morning when a ‘terrific explosion’, viz, the bursting of the boiler, pitched the locomotive on its side, presently a spectacular image of mangled engineering.

Drinkers, staff and residents in the nearby Telegraph Hotel, pictured at the rear of this scene, would no doubt have emerged startled by the noise and anxious about the fate of the train’s operators.

While the engine was lumped on its side, the tender was thrown across the rails, and six trucks and vans were heavily damaged – one of the trucks ended upside down against the embankment.

The derailed train presented a picture of destruction and confusion. Not so much confusion, however, that the bloke pictured here front and centre of the wreck wasn’t happy to pose proudly for the camera. His serious-looking colleagues appear more anxious about the damage effected and how the track might be cleared.

The explosion threw the engine driver, owner of the impressive moniker Auguste de Pazanan, and fireman Thomas Macnamara from the engine. They landed on the embankment and were lucky not to sustain serious injury.

The trucks and their contents, including rod iron, timber and cases of oranges, presented a scene of ruin and industrial/agricultural chaos.

Workmen were engaged all day and night repairing the track and crowds of spectators watched proceedings. Twenty of the workmen came from Williamston and at night some of the timber from the smashed trucks was piled up for bonfires – providing the necessary light for work to continue.

It’s hardly the only disaster to hit the Geelong line. In fact, the line was christened with a disaster.

The official maiden voyage, on June 25, 1857, with the governor Sir Henry Barkly and entourage (his suite, as it were) in the first carriage of the train, journeyed went from Geelong to Williamston and back.

Five hundred guests packed into 10 carriages – government department bosses, train company execs, industry captains, shareholders, the press and other hangers-on. It was a monster occasion, one with some 2000 people at the official dinner that evening in a makeshift dining hall – the railway station’s passenger shed.

But not before tragedy struck. The train pulled out of Geelong 10.30am, all parties laughing and carrying on, and made its way to Cowie’s Creek where the railway company’s superintendent of locomotives, Henry Walters, was standing on the engine holding on to an iron upright. The train was nearing the bridge opposite the Ocean Child as Walters turned about to check the rear of the train.

His head belted a timber beam on the bridge and he fell off the train. Doctors tried what they could but Walters was dead inside four hours.

But the show had to go on, and on it did, reaching Willy by 12.10pm and returning to Geelong by 2.20pm.

Not bad time considering what some present-day football trains can achieve. Mind you, it did stop for water and coal at Werribee.